Cache Valley

When Tara Westover wrote her dissertation “The family, morality, and social science in Anglo-American cooperative thought, 1813-1890” (Westover, 2014), she was writing about the intellectual history of a period when the valley in which she lived as a child was being ‘discovered’, settled, and developed by white men.

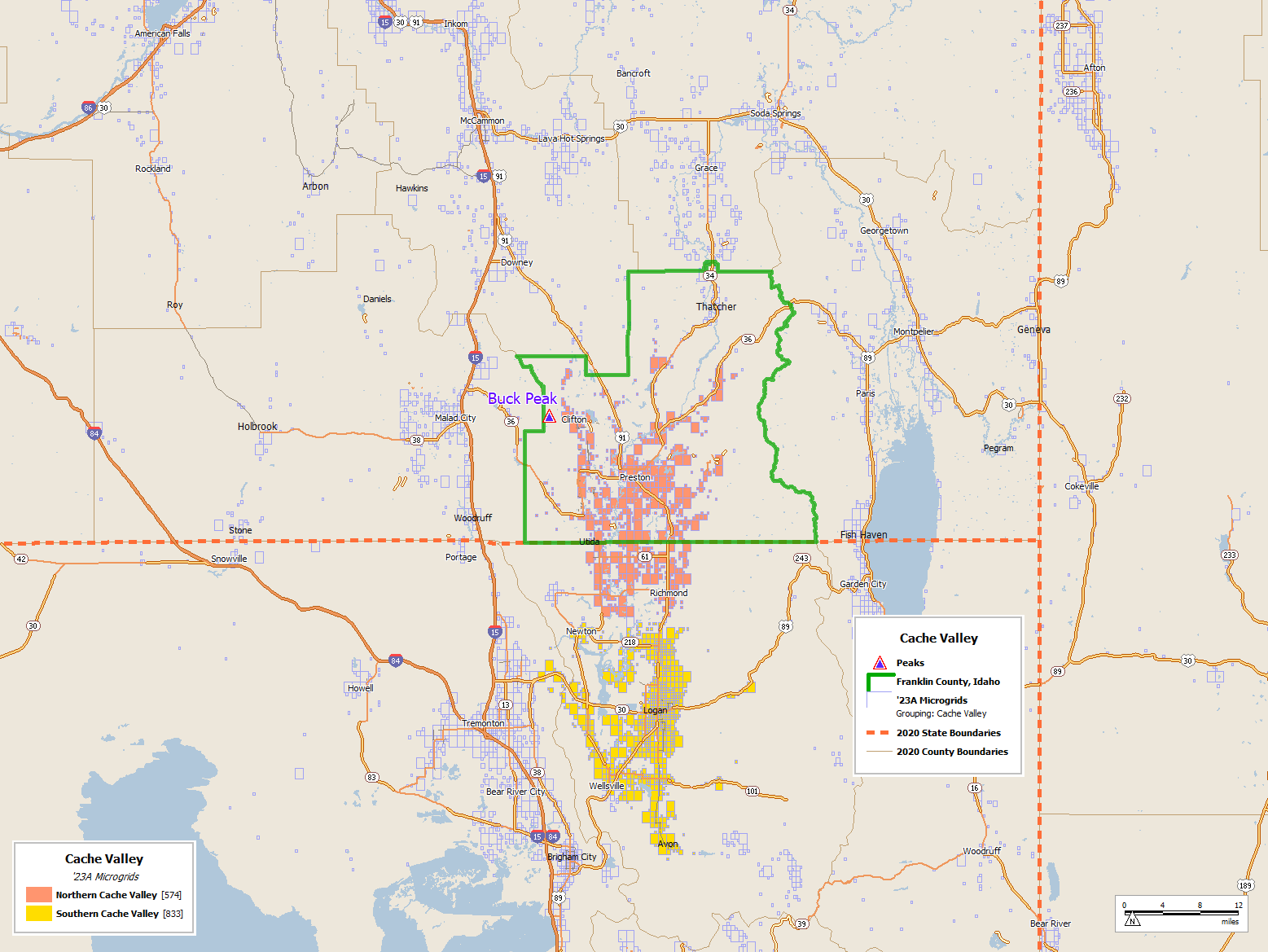

The map above shows tiny rectangles only where there is population, a good basis for a type of thematic map known as a ‘dasymetric’ map when the rectangles are colored in. The ‘dasy’ part of ‘dasymetric’ is derived from the Greek word for density.

I’ve missed visiting northern Cache Valley a couple of times: we once went through Logan then past Bear Lake while driving north from Ogden to Jackson Hole Wyoming for a family vacation. Much later my brother and I concocted a skiing vacation at the deep powder mecca of Grand Targhee, Wyoming, so well hidden that it practically defines the term “secure and undisclosed location”. We drove up Interstate 15 to the West of the Bannock Range and continued on until we got to Alta, Wyoming.

I had never heard of anything in this valley, which remains well hidden and sparsely populated to this day, nor had I ever known of the Bear River Massacre. I attended elementary school (the stage of education when kids learn the most about Native Americans) in Wisconsin, and the big event there was the Peshtigo Fire, which burned most of southern Wisconsin.

Nestled between the Bannock Range to the West, and the Bear River Mountains between the valley and Bear Lake (on the other side of the mountains), the Cache valley, home to the Shoshone, was “discovered” by Jim Bridger in 1818. It was used by fur traders and fur trading companies as an area to cache furs (hence the name), and was settled by its first Mormon settler beginning around 1852.

According to Wikipedia:

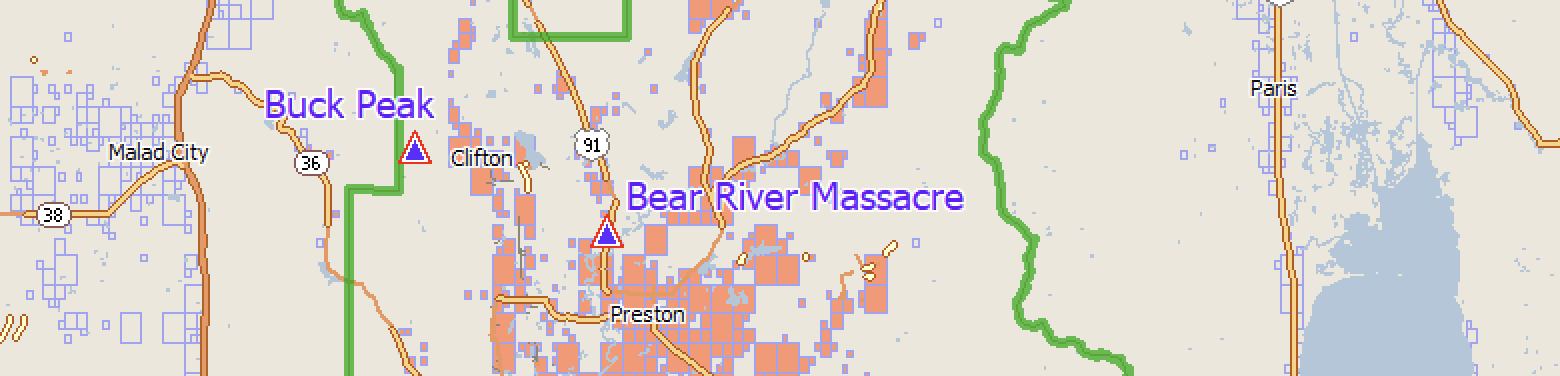

“On January 29, 1863, an expedition from Camp Douglas, Utah to Cache Valley, the United States Army at the request of Cache Valley settlers attacked a Shoshone village in the early morning at the confluence of the Bear River and Beaver Creek (now Battle Creek) in what became known as the Bear River Massacre.[7][8] Officially, numbers of Shoshone dead have varied, but estimates settle around 400-500 dead, including hundreds of women and children.[8] This is still the largest massacre of Native American peoples by the United States government today.[8]“

When I was reading “Educated”, Tara Westover’s influential and gripping memoir, I wondered about the location of Idaho’s Franklin County (shown in green outline on the first map above), and Buck Peak, the mountain behind her house. I was surprised to find it was probably only a little over 90 miles, about an hour and a half drive north from my Utah home in the 1960s, where I lived 25 years before Westover was born.

A few years after I was in Middle School (then called Junior High) in the 1960s, learning Algebra, Geometry, and Trigonometry in Utah, Tara Westover’s mom was in middle school in Preston, Idaho.

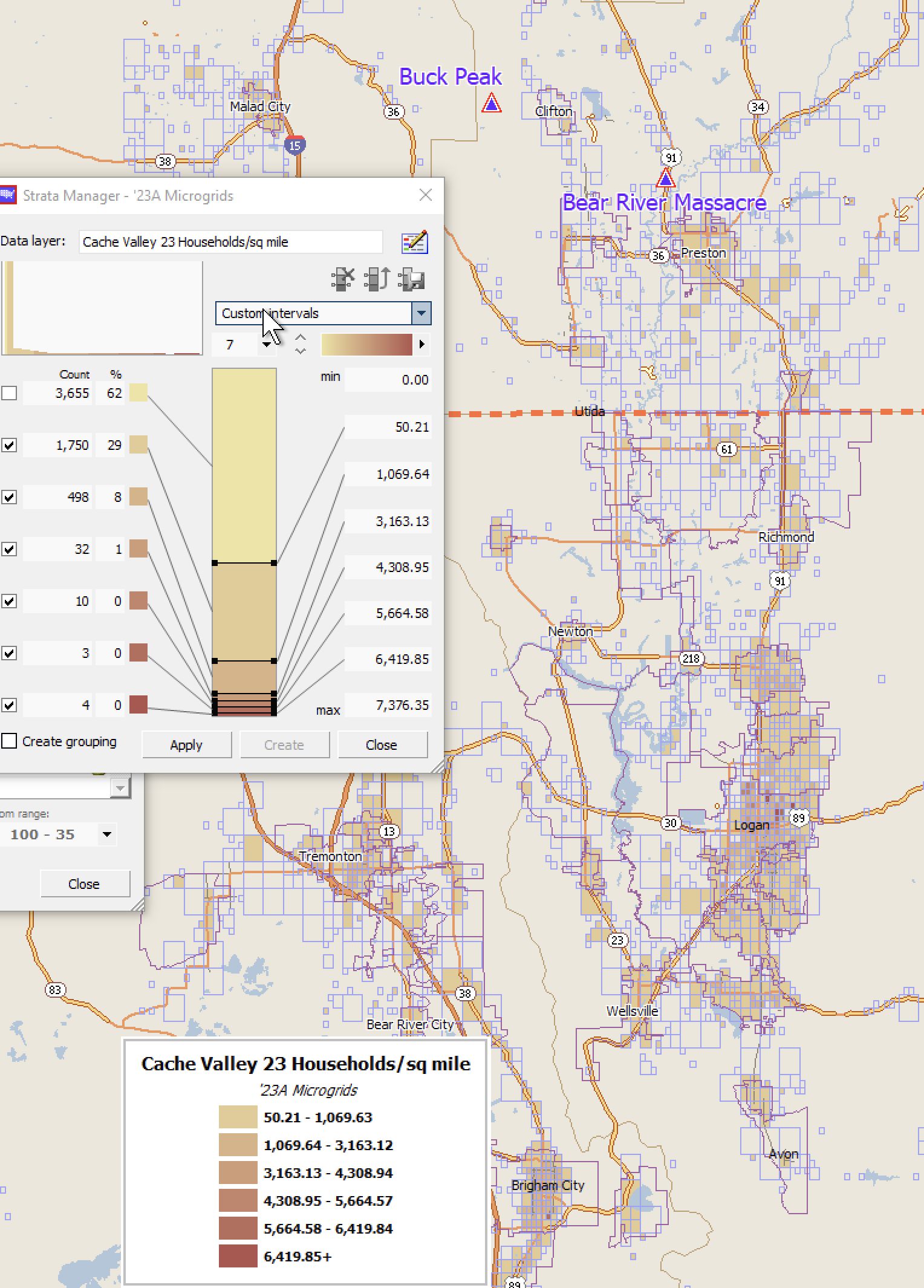

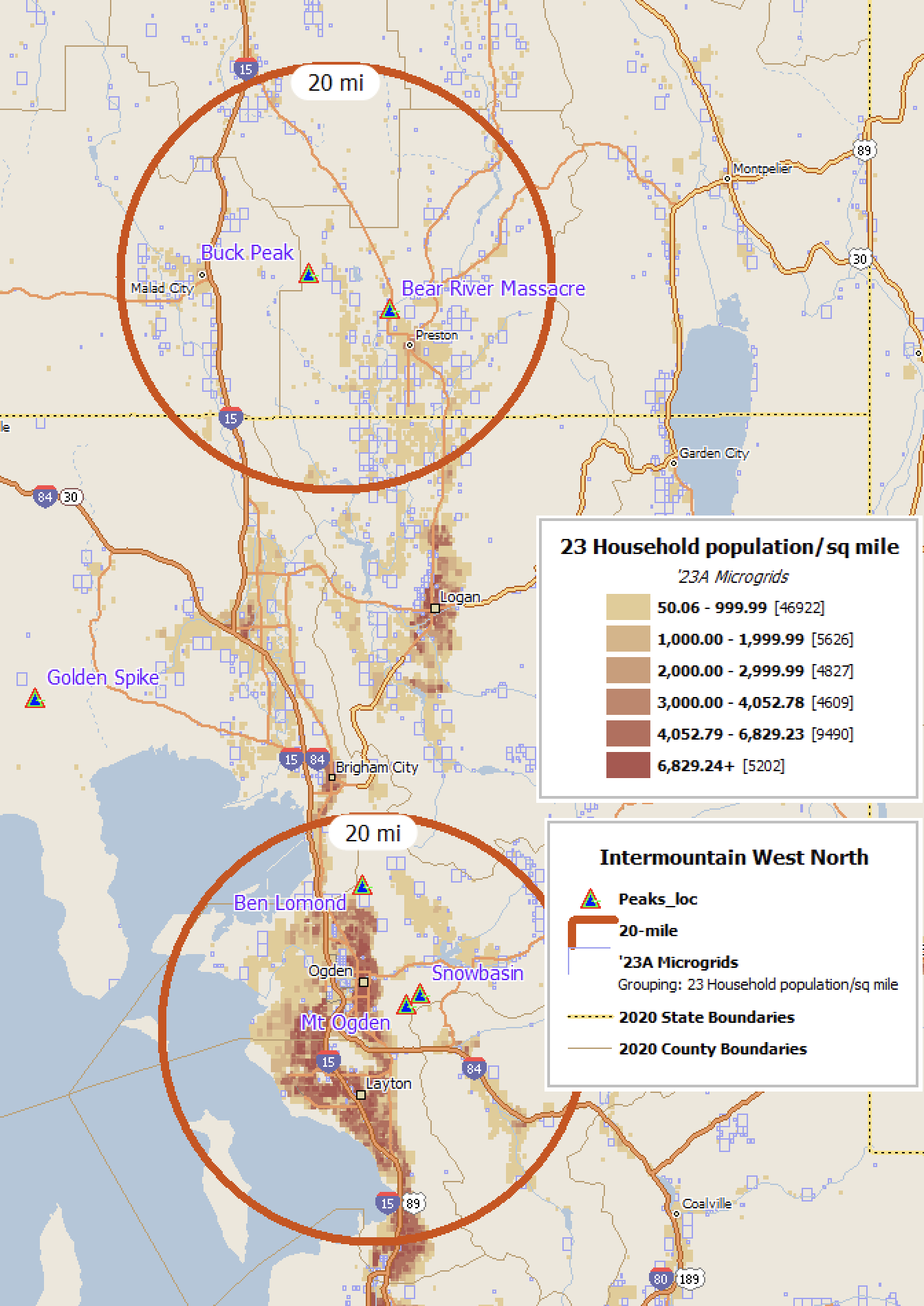

The household density in north Cache is sparse. It was nothing like Ogden or even Logan, so there was probably not a nearby rival junior high school. The map above shows the household density, leaving out grids that don’t have at least 50 households per square mile, while the map below show the density of the household population, leaving out grids where there are fewer than 50 people per square mile living in households, according to the 2023A(Jan1) Scan/US Demographic Estimates.

In addition, a couple of geographic and cultural landmarks have been added to the map above: the location of a popular local ski area (Snowbasin), the location of the Golden Spike, or “Last Spike” of the transcontinental railroad, which was driven by Leland Stanford in 1869, a couple of prominent mountains, and the approximate location of the Bear River massacre.

— all photos Copyright © 2022-2024 George D Girton all rights reserved